Conservation Agriculture: The Great Ally of European Farmers to Secure the Future

Conservation Agriculture: The Great Ally of European Farmers to Secure the Future

2023-06-30

What Is Conservation Agriculture and Why Is It More Beneficial?

2023-10-17Conservation Agriculture: The Great Ally of European Farmers to Secure the Future

Carlos Molina Pitarch, Technical Advisor of the Aragonese Association for Conservation Agriculture (AGRACON)

Using spontaneous summer weeds in dryland farming as a cover crop (CC) to turn a problem into a tool that, if managed properly, can generate countless agronomic and environmental benefits.

The new paradigm of "Evergreen Agriculture" is here to stay. Already considered the fourth pillar of Conservation Agriculture, it is based on the concept of "feeding the soil," meaning nourishing beneficial microbiology—ideally 365 days a year—through a continuous flow of carbon into the soil, produced by the photosynthesis of living plants.

The soil is a living entity that can contain millions of microorganisms, which feed on "solid" carbon (crop residues and roots) and "liquid" carbon through commercial crops and cover crops (root exudates derived from photosynthesis).

Applying these management practices is essential to enhance the biological fertility of agricultural soils, increase their organic matter content, and reduce dependence on external inputs. Long-term implementation will improve crop resilience during prolonged drought periods, which are becoming increasingly common due to the ever-present effects of climate change.

Cover crops (CC) are either sown or spontaneous crops that are managed without commercial purposes. Their inclusion in the Conservation Agriculture system aims to provide a range of agronomic and environmental benefits in the short, medium, and long term, ultimately improving the economic profitability of farming operations by increasing the returns of subsequent commercial crops.

A proper selection of species for cover crops is crucial to maximizing their benefits within the agroecosystem. It is recommended to carefully study the chosen species to ensure they do not serve as a bridge for fungal diseases and pests, which could harm commercial crops, and to prevent the creation of weed seed banks that might later compete with future crops.

When using sown cover crops, it is advisable to plant mixtures of at least two or three species to generate complementary benefits (nitrogen fixation, soil coverage, improved structure through taproots, etc.) and maximize their impact.

This strategy seeks to synchronize commercial crops with cover crops to maximize the number of days throughout the agricultural cycle during which living plants perform photosynthesis in the fields and inject carbon into the soil.

In most semi-arid drylands and a significant portion of sub-humid drylands of the Iberian Peninsula, summer crops such as sunflowers are not typically grown due to climatic conditions, and rotations consist entirely of winter-cycle commercial crops. As a result, a high percentage of opportunities to implement cover crops occur during the summer fallow period, between June (harvest) and October (sowing).

The climatic conditions of the Mediterranean basin, characterized by high probabilities of no rainfall throughout the summer (except for occasional torrential storms) combined with extreme temperatures and frequent heat waves, make it unfeasible to replicate the French model of sown cover crops in extensive farming systems.

This raises two key questions: What is the best cover crop for dryland farming? Which species are best adapted and capable of thriving under drought conditions?

The Answer Lies in Nature: Spontaneous Summer Weeds

What if we have been following the wrong paradigm all along? What if some "weeds" are not as harmful as we think or have been led to believe? What if, instead of eradicating weeds like Salsola kali, we manage them as beneficial tools for our dryland agroecosystems? What if the idea of having no plants in the fields all summer was wrong? What if we could keep dryland fields green in summer? What if we transformed solar energy into organic matter through living plants?

For decades, the agricultural sector has upheld the belief that only commercial crops should exist in the fields throughout the agricultural cycle, and everything else should be eradicated—through repeated tillage and/or the application of agrochemicals. To challenge this paradigm, readers of this technical-educational article should ask themselves:

What is truly a weed?

The answer is: A weed is any plant species that directly competes with a commercial crop for water, nutrients, space, and/or light. If one or more of these conditions are met, the species can be classified as a weed—for example, Bromus in a wheat field.

Many farmers who manage their operations based on Conservation Agriculture principles have started asking these questions over the past decade and arrived at the following realization:

"For years, I have been fighting to eradicate summer weeds like Salsola kali. However, this weed does not directly compete with my winter-cycle commercial crop. Therefore, instead of trying to exterminate it—which I never truly can—I will stop seeing it as a problem and start managing it as a tool to extract the maximum benefit at the lowest management cost."/p>

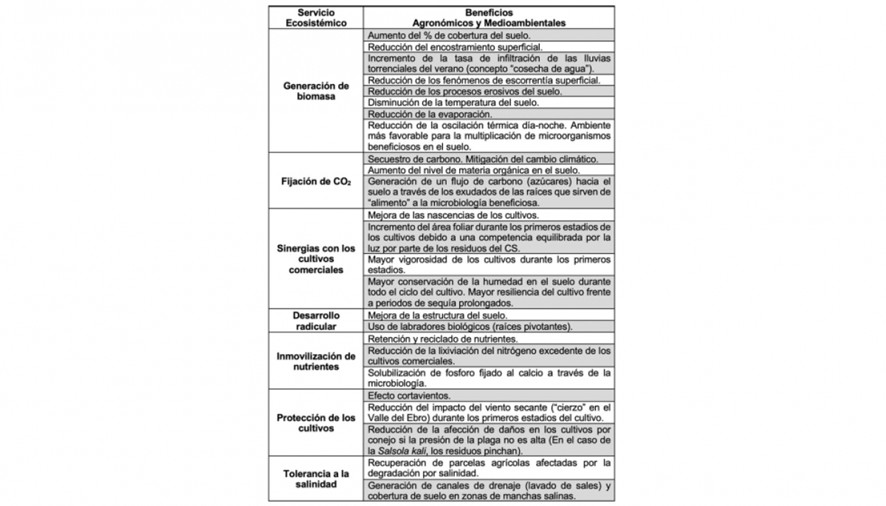

The implementation of spontaneous summer weed cover crops in dryland agricultural systems can generate the following ecosystem services and agronomic and environmental benefits (see table).

To maximize all these agronomic and environmental benefits while avoiding issues when establishing commercial crops after spontaneous summer cover crops, it is essential to follow specific management criteria based on the rotation crops and the type of no-till seeder used.

Cover crop management can be carried out using different methods, including grazing, roller-crimping, mowing, and/or applying an agrochemical product.

This post is also available in: Español (Spanish)